Until I began playing tennis in 2023, my sports were baseball and golf. Baseball (and I gather Cricket) may be the two most elementally unchanged ball sports. Sure, we’ve been living in baseball’s live-ball era since the time of Babe Ruth but other than that, little has changed between the baseball and the bat over the last century.

Golf is totally different story with technical advancements in ball and club (especially driver) construction that has fundamentally changed the game forever if not for better. The impact of multilayer balls and max-COR drivers is inarguable and these improvements have been augmented by the practice of data-based club and shaft fitting. Today, the average recreational players can avail themselves of most of the tech a touring pro can. Of course, the tour pro doesn’t pay.

I see tennis somewhere between those extremes. Until recently, my favorite racket was a borrowed 2014 Head Prestige Pro. It’s still my favorite racket but my advancing years have suggested that lighter may be better for my game if not my ego. Still, the fact that a twelve year old frame could still be useful to a player at my level gives me great respect for what a great racket Head could build all those years ago and a little less respect for their 2025 offerings which I am sure they describe as far more advanced than my old Prestige.

What all this means is I can easily imagine a day when a tennis player, pro or amateur, can have their tennis racket (and strings) evaluated by measured data. Golf has already done this and more. Golf tour pros, with their unimaginably consistent swings, can tune their clubs to their ball of choice, chasing their ideal of ball speed, spin and feel. I would be surprised if players on the WTA and ATP can’t do something similar right now. And, if they can, you and I will be able to soon. Whether this will help the game of mere mortals like me is anyone’s guess.

I am so glad anyone seeking beneficial alteration of their tennis racket can reach out to Miha Flisek of Impacting tennis. Even tbough my skills were still in their infancy when I first started playing tennis I knew and could feel that details mattered. In fact, everything mattered. The marriage of string, racket velocity, racket weight, weight distribution, racket flex (on multiple axes) and swing shape are a fascinating combination of variables and destined to confuse most players, leading to a great deal of misunderstanding.

I sought to learn all I could, sometimes surprised by how such complicated issues were spoken of with such a cavalier attitude. I was lucky my early searches pointed me toward Miha and his excellent videos. HIs clarity did a lot to demystify that which could easily be mystifying. I’m grateful Miha was generous enough to contribute his time to answering my questions about him and Impacting Tennis.

Tennis thing: Tell me a little about your own history playing tennis? How old were you when you started?

Miha Flisek: I started playing tennis very early, but at the same time I was also into archery and basketball. It wasn’t until an injury took contact sports off the table that I really began focusing on tennis. From the beginning, I was very sensitive to equipment. In archery, even the smallest change can completely alter your shot, and I brought that same mindset into tennis. I was honestly surprised how little attention most tennis players gave to their rackets.

Later in college, I started combining my background in engineering with my growing understanding of tennis equipment. That’s when things really started to click. I began connecting the dots between player movement, stroke mechanics, and racket behavior. That’s how Impacting Tennis was born, from the idea that tennis gear shouldn’t be treated as an afterthought but as a core part of performance.

Tennis thing: How long did it take for you to begin customizing your own rackets? What were some of your early modifications?

Miha Flisek: I started modifying my rackets almost immediately, experimenting with strings, shifting balance points, and later adding lead tape. At the very beginning, I didn’t even have proper materials. I remember finding some old lead pipes and literally hammering them flat to make my own thin strips of lead, that was my first version of lead tape. It was very DIY, but it gave me a hands-on feel for how mass placement affects the racket.

The real transformation came later when I gained the technical knowledge to calculate what I was doing. Instead of just feeling the difference, I could measure swingweight, balance, MGR/I, twistweight, and understand what each change was actually doing. That’s when customization stopped being trial and error and started becoming engineering and that’s really what laid the groundwork for everything I do now.

Tennis thing: When players come to you for customization, do they usually have a specific goal in mind, or do they rely on your guidance to help them improve?

Miha Flisek: Players usually come in with a clear goal in mind, whether it’s more spin, more control, or more stability, and I help them move toward it. But we never start with the racket. First, we look at where the player is in their career, what’s limiting their game, what they’re trying to improve. We take into account their technique, movement patterns, and overall development.

Only after that do we adapt the equipment. The racket becomes a tool that supports their goals. When you get it right, it’s not just a better racket, it’s a better version of their game.

Tennis thing: One of the most interesting aspects of tennis for me are the significance of audible cues. The Octo damper is designed to reduce unwanted vibrations while keeping the higher-frequency feedback that’s important for feel, timing, and contact cues. What led you to choose the thermoplastic elastomer PEBA (Polyether block amide) and were there other materials you considered?

Miha Flisek: I was already working with PEBA on a different project and found the material really interesting. It was being used in high-performance running shoes for its energy return properties, and it had just started to become available for 3D printing.

The Octo damper actually came out of working with the material. I realized it had the ideal combination of characteristics, soft enough to reduce unwanted low-frequency vibration, but responsive enough to preserve the high-frequency feedback that’s so important for timing and feel. It wasn’t something I set out to create, it just made perfect sense once I started using the material.

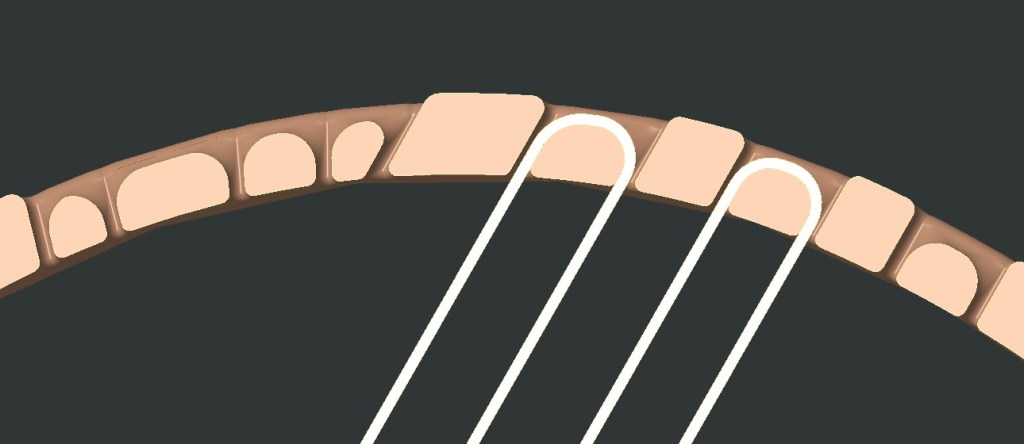

Tennis thing: I am really fascinated that you actually 3D printed a tennis racket! Without getting too deep into the technical weeds, how many separate pieces were needed to create TO Stardust and what adhesive did you use? Also, I found your use of rounded string transitions rather than traditional grommets to be exceptionally clever. What was the total print time?

Miha Flisek:TO Stardust was printed as a single solid frame. No adhesives, no bonding. Just one continuous piece. That required a very large and advanced 3D printer along with specialized materials. The handle pallets and buttcap were added afterward, like with a standard racket.

The total print time was about 12 hours. One of the standout features is the integrated rounded string holes, which replace traditional grommets. That not only reduces unnecessary components but also gives the stringbed a more consistent response. The project was a way to test what happens when you throw out legacy design assumptions and build a racket from the ground up using modern tools.

Tennis thing: Many ATP players still use racket designs that are more than a decade old, often under new paint jobs. Do you think racket technology has plateaued or do you see meaningful trends in design or construction that could still benefit players?

Miha Flisek: I don’t see any real leaps in racket technology happening right now. The core materials, like carbon fiber laminates, have been around for a long time, and most of the available geometries and design concepts have already been explored or exhausted. There’s not much on the horizon in terms of radically different materials that would offer meaningful improvements.

What we are seeing today, like the shift toward lighter and more powerful rackets, isn’t so much about technological progress as it is about adjusting to external changes, especially the balls. Balls have become lighter and less consistent, which makes it harder to get penetration through the court, so players are shifting toward rackets that help generate more pace and spin.

The next real shift in racket design will probably come with the maturation of 3D printing technology, particularly once continuous carbon fiber printing becomes viable. That’s when we’ll finally be able to explore forms, layups, and mass distributions that are simply impossible to achieve with traditional molding techniques.

Tennis thing : What’s next for Impacting Tennis? What enhancements can we expect to see in TO Stardust v2?

Miha Flisek:That ties directly into the future of TO Stardust. Right now, with the current 3D printing materials and processes, it’s not quite at the performance level I want, at least not for professional-level play. The design itself showed what’s possible in terms of rethinking racket construction, like grommetless string transitions and integrated frame geometry, but to move to the next stage, we’re waiting for the technology to catch up, especially in terms of continuous fiber reinforcement.

In the meantime, my focus is on consulting and helping players unlock performance through better equipment understanding and customization. I’m also exploring string design using a novel material that hasn’t been used in tennis yet. The long-term goal remains the same: use engineering and first principles to push tennis forward, not just follow trends.

Tennis thing: Thanks for participating, Miha. I will be posting my review of the Octo damper soon. I’ve been evaluating along with a trusted pro at my club. So far, I am really liking it, especially its amazingly light weight.

Leave a comment